When you request a religious accommodation at work—whether for prayer breaks, dress requirements, or schedule changes—your employer has to provide it unless doing so creates an “undue hardship.” Understanding this standard is critical because it determines whether your employer can legally deny your accommodation request.

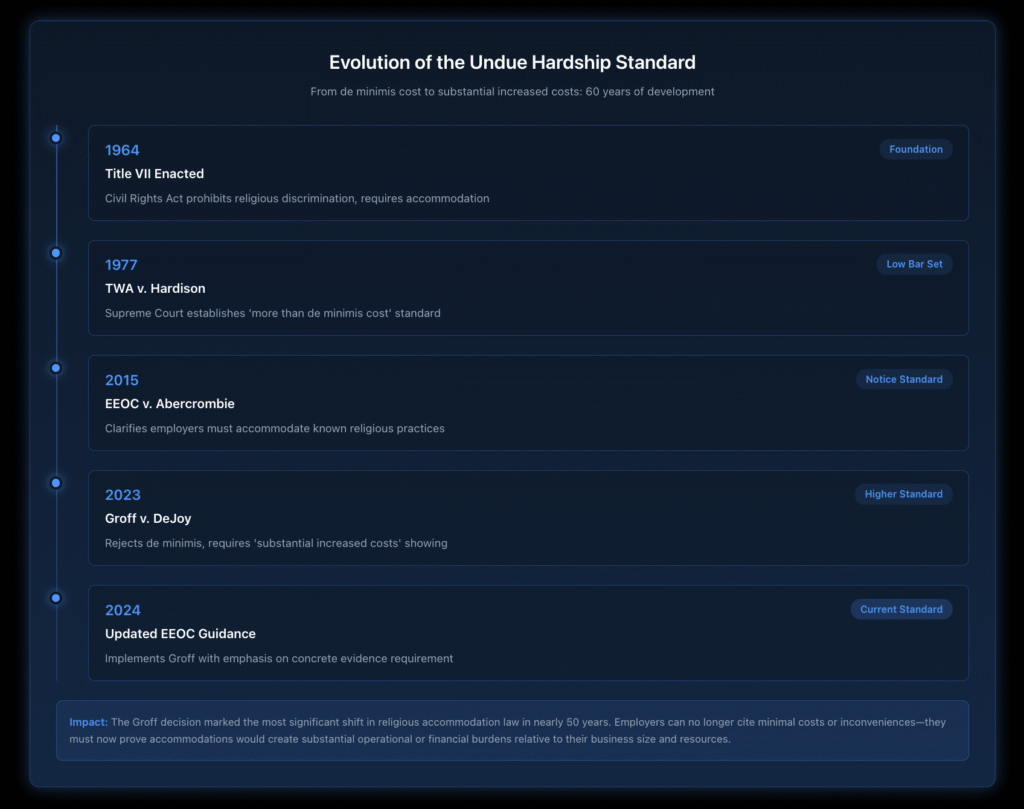

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, employers must reasonably accommodate your sincerely held religious beliefs unless the accommodation causes more than a minimal burden on business operations. This means employers have a relatively low bar to clear when refusing accommodations—they don’t need to prove catastrophic consequences, just that the accommodation would impose “more than a de minimis cost.”

Key Takeaways

- Employers must accommodate religious practices unless doing so creates “undue hardship”.

- The undue hardship standard for religion is lower than for disability accommodations.

- De minimis cost (more than minimal burden) is enough to justify denial.

- Factors include financial cost, disruption to operations, and burden on coworkers.

- The EEOC recently clarified that employers must show “substantial increased costs” to prove undue hardship.

- New York law provides additional protections that may be broader than federal law.

- Employers must engage in an interactive process before denying accommodation requests.

Disclaimer: This article provides general information for informational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for legal advice. It is essential to consult with an experienced employment lawyer at our law firm to discuss the specific facts of your case and understand your legal rights and options. This information does not create an attorney-client relationship.

How Does the Undue Hardship Standard Apply to Religious Accommodations?

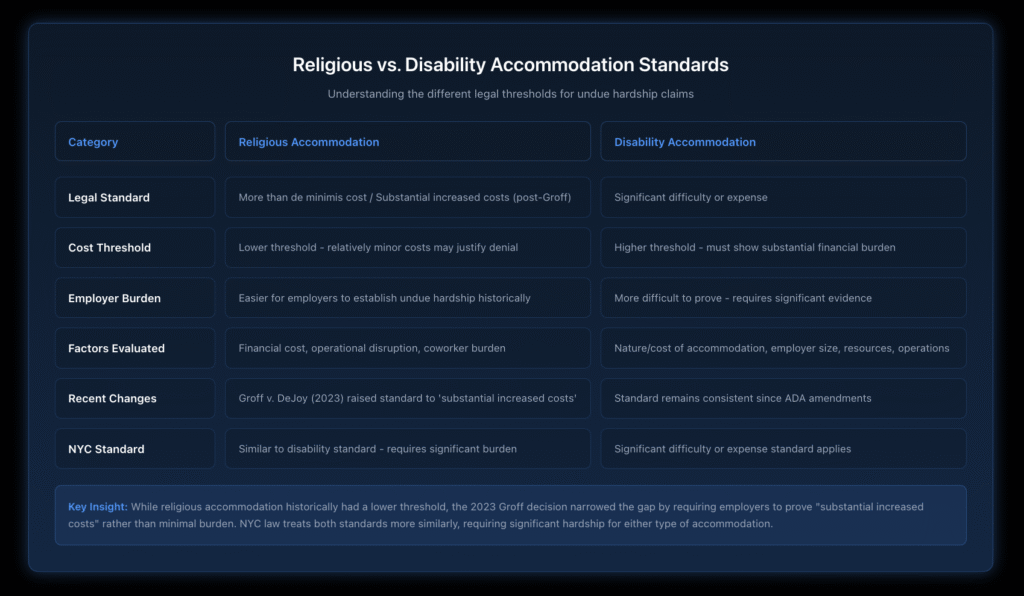

The undue hardship standard for religious accommodations differs significantly from disability accommodations under the ADA. For religious accommodations, employers can deny your request if it causes “more than a de minimis cost”—meaning more than a minimal burden on the business. This threshold is much lower than the “significant difficulty or expense” standard used for disability accommodations under the ADA.

This de minimis standard has been controversial because it allows employers to reject accommodations for relatively minor costs or inconveniences. Recent guidance from the EEOC has attempted to raise this bar slightly, requiring employers to demonstrate “substantial increased costs” rather than just minimal inconvenience.

What Three Factors Determine Undue Hardship?

Courts and the EEOC evaluate three primary factors when determining whether a religious accommodation creates undue hardship:

Financial Cost: The monetary expense of providing the accommodation, including both direct costs (like hiring a substitute worker) and indirect costs (such as administrative burden). However, the expense must be substantial relative to the employer’s size and budget—a $500 cost might be significant for a small business but minimal for a large corporation with substantial resources.

Workplace Disruption: The impact on business operations, workflow, and other employees. This includes whether the accommodation affects productivity, safety protocols, or the ability to serve customers. For example, allowing extended prayer breaks might create undue hardship if it prevents a manufacturing line from operating efficiently.

Burden on Coworkers: The effect on other employees, including whether they must take on additional duties, work less desirable shifts, or face scheduling complications. However, coworker complaints or discomfort alone don’t constitute undue hardship—the burden must be objective and measurable.

How Has the Definition of Undue Hardship Recently Changed?

In 2023, the Supreme Court clarified the undue hardship standard in Groff v. DeJoy, rejecting the decades-old interpretation that “more than de minimis cost” was sufficient. The Court held that undue hardship requires “substantial increased costs” in relation to the conduct of the employer’s business, not just any minimal burden.

This shift means employers must now demonstrate more significant impacts before denying religious accommodation requests. The EEOC has updated its guidance to reflect this standard, emphasizing that:

- Speculative hardship isn’t enough—employers must show actual, concrete impacts

- Temporary inconveniences don’t typically qualify as undue hardship

- The size and resources of the business matter when evaluating costs

- Employers must explore multiple accommodation options before claiming hardship

What Are Examples of Reasonable Religious Accommodations?

Employers typically must provide accommodations like flexible scheduling for religious observances, dress code exceptions for religious attire, and workspace modifications for prayer. These accommodations rarely create undue hardship unless they fundamentally alter business operations or impose substantial costs.

What Counts as a Reasonable Accommodation Request?

Common reasonable accommodations include:

Schedule Changes: Allowing flexible work hours for prayer times, religious holidays, or Sabbath observance. This might include shift swaps, alternative schedules, or using vacation time for religious observances.

Dress and Grooming: Permitting religious head coverings, beards, or modest clothing even when they don’t align with standard company dress codes. For example, allowing a Muslim woman to wear a hijab or a Sikh man to wear a turban and maintain an uncut beard.

Prayer Breaks: Providing brief, unpaid breaks during the workday for prayer or religious rituals. This might mean allowing a Muslim employee to step away for five minutes during designated prayer times throughout the day.

Dietary Restrictions: Making adjustments for religious dietary laws in workplace cafeterias, company events, or client dinners. This includes accommodating kosher, halal, or vegetarian requirements tied to religious beliefs.

Job Reassignment: Moving an employee to a different position or department when their current role conflicts with religious beliefs. For instance, transferring a pharmacy employee who objects to dispensing contraceptives based on religious convictions.

What Should You Write in a Religious Accommodation Request?

When requesting a religious accommodation, be clear, specific, and professional. Your written request should include:

Your Sincerely Held Belief: Explain the religious practice or belief requiring accommodation. You don’t need to provide extensive theological justification, but state that the practice is rooted in sincere religious conviction.

Specific Accommodation Needed: Detail exactly what change you’re requesting. Instead of saying “I need time off for religious reasons,” specify “I need to be excused from work between 6-8 PM every Friday for Sabbath observance.”

How It Affects Your Work: Address potential concerns about your ability to meet job requirements. Offer solutions like shift swaps, making up hours, or adjusting responsibilities to minimize impact on operations.

Alternative Solutions: Suggest multiple accommodation options if possible. This shows flexibility and helps your employer find a solution that works for both parties.

You’re not required to prove that your religious belief is mandated by your faith or widely practiced by others in your religion. Courts protect individually held sincere beliefs, even if they’re not central tenets of an organized religion.

What Qualifies as Sufficient Undue Hardship to Deny Accommodation?

Undue hardship typically requires demonstrating substantial increased costs, significant operational disruption, or measurable safety risks—not just inconvenience or coworker complaints. Employers must prove actual hardship with concrete evidence, not speculation about potential problems.

What Is an Example of Undue Hardship in Religious Accommodation?

Legitimate Undue Hardship Examples:

A hospital might establish undue hardship if accommodating a nurse’s request to avoid working Saturdays requires paying substantial overtime to other nurses, disrupts patient care coordination, and exceeds reasonable costs given staffing constraints. The key is that multiple factors combine to create a significant operational burden.

A small restaurant with three servers on staff might demonstrate undue hardship if accommodating an employee’s twice-daily 30-minute prayer breaks during peak lunch and dinner service prevents adequate customer service and requires hiring additional staff at costs that significantly impact the business’s viability.

Not Sufficient Undue Hardship:

Customer preference or comfort doesn’t justify denying accommodations. If customers complain about an employee wearing a hijab, yarmulke, or other religious attire, this doesn’t constitute undue hardship—employers must protect employees from discrimination, not cater to discriminatory preferences.

General coworker resentment about covering shifts for someone’s religious practices typically doesn’t establish undue hardship. While measurable burden on coworkers can contribute to hardship, simple complaints or discomfort aren’t enough—the employer must show concrete operational impacts.

How Hard Is It to Prove Undue Hardship Exists?

Proving undue hardship has traditionally been relatively easy for employers under the old “de minimis” standard. However, after the Groff decision, employers now face a higher bar and must provide concrete evidence of “substantial increased costs” rather than hypothetical concerns.

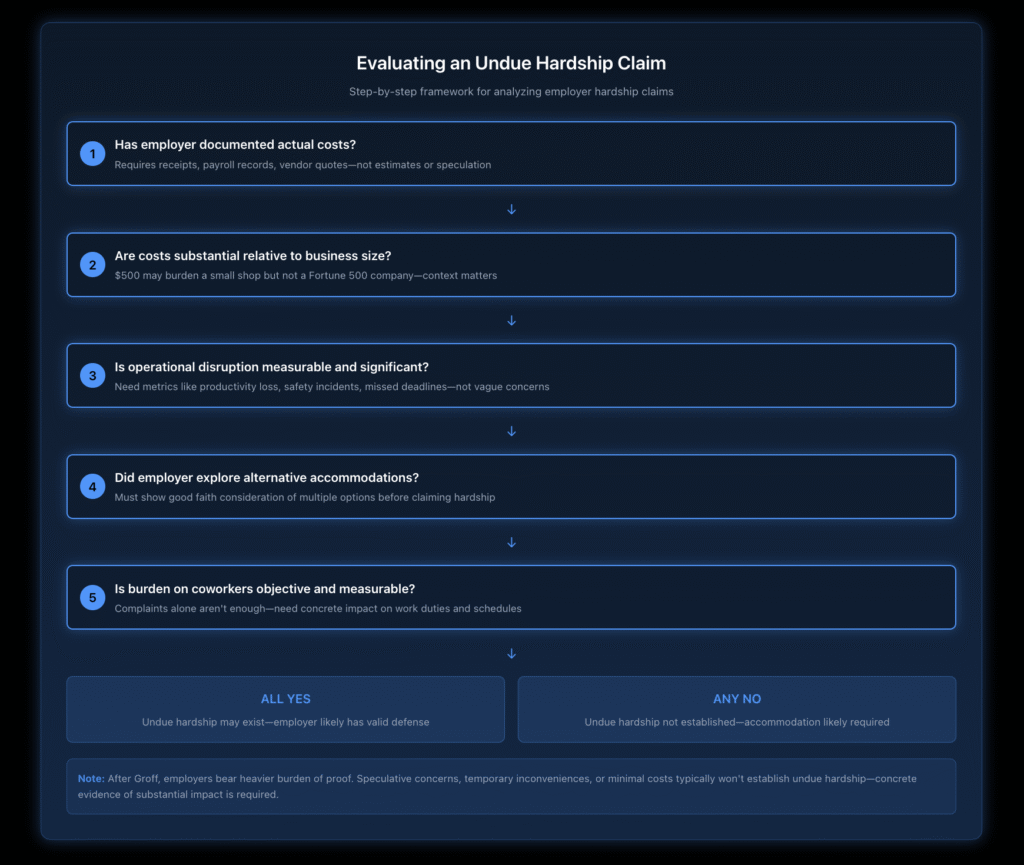

Employers must document:

Actual Costs: Specific financial impacts with supporting documentation, not estimated or speculative costs. This includes receipts, payroll records, or quotes from vendors for additional services needed.

Operational Impact: Real-world disruption to business functions, measured through metrics like productivity loss, customer complaints, missed deadlines, or safety incidents. Vague claims about “morale problems” or “scheduling difficulties” typically won’t suffice.

Good Faith Exploration: Evidence that the employer genuinely considered alternative accommodations before claiming undue hardship. Courts look unfavorably on employers who immediately reject requests without exploring compromise solutions.

Proportional Analysis: Consideration of the employer’s size, budget, and resources. What constitutes substantial cost for a small business differs dramatically from a large corporation. A Fortune 500 company can’t claim undue hardship for costs that would barely register in its operating budget.

What Are Examples of Unreasonable Religious Accommodation Requests?

While employers must accommodate sincere religious beliefs, some requests exceed legal requirements:

Requests that violate legal obligations or safety standards typically aren’t protected. For example, a truck driver can’t refuse to transport alcohol if that’s a core job function, and a security guard can’t refuse to carry a required firearm based on pacifist beliefs without considering transfer to a non-armed position.

Accommodations that completely eliminate essential job functions generally create undue hardship. If you’re hired specifically to work weekends and your religion prohibits weekend work, the employer might not be able to accommodate this without fundamentally altering the position.

Requests that require other employees to violate their own religious beliefs can be unreasonable. However, neutral duties like serving alcohol to customers or processing paperwork for procedures an employee personally objects to usually don’t implicate other employees’ religious freedom.

How Do You Prove Religious Discrimination When Accommodation Is Denied?

To prove religious discrimination after a denied accommodation, you must show you informed your employer of your religious need, a reasonable accommodation existed that wouldn’t cause undue hardship, and the employer refused to accommodate despite available alternatives.

Who Decides Whether Something Constitutes Undue Hardship?

Initially, your employer evaluates whether an accommodation creates undue hardship. However, employers can’t make this decision unilaterally without engaging in an interactive process with you. Under both federal law and New York State Human Rights Law, employers must discuss accommodation options and explore alternatives.

If you disagree with your employer’s hardship assessment, you can:

File an EEOC Charge: Submit a discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission within 300 days of the denial in New York (180 days in states without equivalent state laws). The EEOC will investigate whether undue hardship actually existed.

File with New York State Division of Human Rights: New York employees have up to one year to file discrimination complaints with the state agency, which often provides broader protections than federal law.

File with NYC Commission on Human Rights: New York City residents have three years to file complaints and may benefit from the NYC Human Rights Law’s expansive interpretation of religious protections.

Pursue Legal Action: After receiving a “right to sue” letter from the EEOC or state agency, you can file a lawsuit in federal or state court, where a judge or jury will evaluate whether legitimate undue hardship existed.

How Do You Demonstrate Undue Hardship Wasn’t Present?

Building your case requires:

Document Everything: Keep copies of your accommodation request, your employer’s denial, and all correspondence about the accommodation. Save emails, text messages, and notes from meetings discussing your request.

Identify Alternative Solutions: Show that reasonable alternatives existed that your employer didn’t consider. If you requested Fridays off for religious observance, document that shift swaps with willing coworkers were available, but the employer refused to allow them.

Challenge Cost Claims: If your employer claims undue hardship based on costs, gather evidence showing that he actual financial impact would be minimal. Research comparable accommodations at similar businesses, or demonstrate that the claimed costs are exaggerated or don’t account for the employer’s financial resources.

Show Inconsistent Treatment: Demonstrate that your employer accommodates similar requests for other employees. If the company allows schedule flexibility for parents’ childcare needs but denies religious schedule changes, this suggests the claimed hardship is pretextual.

Expert Testimony: In litigation, employment law experts can testify about industry standards for religious accommodations and whether your employer’s claimed hardship is reasonable compared to similar businesses.

Can You Sue for Stress and Anxiety from Denied Accommodations?

Yes, if your employer’s denial of religious accommodation causes emotional distress, you may recover damages for mental anguish in addition to other remedies. However, you must prove the emotional harm resulted from the discrimination, not just workplace stress generally.

Damages in religious discrimination cases can include:

Compensatory Damages: Payment for emotional distress, mental anguish, loss of enjoyment of life, and other non-economic harm caused by the discrimination. You’ll typically need documentation from mental health professionals to support these claims.

Back Pay and Lost Wages: If you were fired, demoted, or lost income due to the denied accommodation, you can recover lost earnings plus benefits.

Front Pay: In cases where reinstatement isn’t practical, courts may award future lost earnings to compensate for ongoing career impacts.

Punitive Damages: If your employer acted with malice or reckless indifference to your rights, courts can award punitive damages to punish egregious discrimination (though these aren’t available against government employers).

The severity of emotional distress matters. Courts award larger damages when denied accommodations cause diagnosed conditions like anxiety disorders, depression, or PTSD, especially when supported by medical records and treatment history.

What New York-Specific Protections Apply to Religious Accommodations?

New York provides robust protections beyond federal law. New York State Human Rights Law prohibits religious discrimination by all employers regardless of size, while Title VII only applies to employers with 15 or more employees. This means even very small businesses in New York must accommodate religious practices absent undue hardship.

How Does NYC Human Rights Law Differ from Federal Standards?

New York City’s Human Rights Law offers the nation’s most protective religious accommodation standards. Key differences include:

Broader “Religion” Definition: NYC law protects religious observance and practice even more broadly than federal law, explicitly covering atheism, agnosticism, and non-theistic beliefs.

Lower Hardship Threshold: While federal law now requires “substantial increased costs” after Groff, NYC law has long interpreted undue hardship even more strictly, requiring significant difficulty or expense similar to disability accommodation standards.

Mandatory Interactive Process: NYC employers must engage in a cooperative dialogue with employees requesting accommodations. Failing to participate in this process can itself constitute discrimination, even if an accommodation might have created undue hardship.

Three-Year Filing Deadline: While EEOC charges must be filed within 300 days and state complaints within one year, NYC complaints can be filed up to three years after discrimination occurs, giving employees more time to pursue claims.

What Happens During an Interactive Accommodation Process?

New York law requires employers to engage in a good-faith interactive process when you request religious accommodation:

Initial Discussion: Your employer must meet with you to understand your religious practice and accommodation needs. They can ask clarifying questions about what you need and why, but can’t interrogate you about the validity of your religious beliefs.

Exploring Options: Together, you and your employer must discuss possible accommodations. The employer should present why certain options might not work and explore alternatives. This isn’t a one-sided conversation—both parties must participate constructively.

Documentation: The employer should document the interactive process, including what accommodations were considered and why particular options were rejected. This documentation becomes crucial if disputes later arise about whether the employer acted in good faith.

Timely Resolution: Employers must respond to accommodation requests promptly. Unreasonable delays in the interactive process can violate accommodation obligations, especially if you face adverse consequences (like discipline or termination) while waiting for a response.

Avoiding Retaliation: Employers cannot retaliate against you for requesting religious accommodation or participating in the interactive process. This protection applies even if your request is ultimately denied based on legitimate undue hardship.

Ready to Take Action?

If your employer denied your religious accommodation request or failed to engage in a good-faith interactive process, you may have grounds for a discrimination claim. The undue hardship standard requires employers to demonstrate substantial costs or significant operational disruption—not just inconvenience or coworker complaints.

Don’t let your employer’s unsubstantiated hardship claims go unchallenged. Nisar Law Group has extensive experience representing New York employees in religious discrimination cases, helping clients secure accommodations and hold employers accountable for discrimination. Contact us today for a consultation to discuss your religious accommodation rights and legal options.

Frequently Asked Questions About Religious Accommodation and Undue Hardship

Undue hardship requires employers to demonstrate substantial increased costs in relation to their business operations, significant disruption to workplace functions, or measurable safety risks. After the Supreme Court’s Groff decision, employers can no longer rely on minimal or speculative costs. The hardship must be concrete, documented, and proportional to the employer’s size and resources, not just theoretical concerns about scheduling difficulties or coworker complaints.

Religious accommodation undue hardship requires showing substantial increased costs, while disability accommodation under the ADA requires significant difficulty or expense—a higher threshold. Federal courts have historically given employers more leeway to deny religious accommodations, though the Groff decision narrowed this gap. In New York City, the standards are more aligned, with both requiring substantial burden on the employer before accommodation can be denied.

A hardship accommodation creates some inconvenience or cost for the employer, but remains reasonable and required by law. An undue hardship creates substantial increased costs or significant operational disruption that exceeds what the law requires employers to bear. The distinction depends on factors like the employer’s size, resources, and the specific impact of the accommodation on business operations rather than arbitrary thresholds.

Courts analyze financial cost relative to the employer’s budget and resources, operational disruption to business functions and workflow, and measurable burden on coworkers’ work duties and schedules. These factors must be substantial and documented with concrete evidence rather than speculative concerns. The analysis is fact-specific, considering the unique circumstances of each workplace and accommodation request.

After the Groff Supreme Court decision, proving undue hardship is more difficult for employers because they must demonstrate substantial increased costs rather than just a minimal burden. Employers need concrete documentation of financial impacts, measurable operational disruption, and evidence that they genuinely explored alternative accommodations. Speculative or exaggerated claims typically fail, especially when the employer has adequate resources or hasn’t engaged in a good-faith interactive process with the employee.

File a complaint with the EEOC within 300 days, the New York State Division of Human Rights within one year, or the NYC Commission on Human Rights within three years. These agencies investigate whether legitimate undue hardship existed or if the employer discriminated against you. You can also request mediation to resolve the dispute. If administrative remedies don’t succeed, you can file a lawsuit after receiving a right-to-sue letter, where a court will evaluate the employer’s hardship claims.

No. Coworker discomfort, complaints, or resistance to covering shifts for someone’s religious practices don’t establish undue hardship by themselves. The employer must show objective, measurable burdens on operations or other employees’ work duties. General resentment or prejudice against religious practices can’t justify denial. However, if accommodation objectively prevents the workplace from functioning or places unreasonable burdens on coworkers’ essential job duties, this may contribute to an undue hardship finding.

State your sincerely held religious belief requiring accommodation, specify exactly what accommodation you need, explain how it affects your work, and suggest possible solutions. You don’t need to prove your belief is mandated by your religion or provide an extensive theological explanation. Focus on clarity and specificity about the practical adjustment needed. Offer to discuss alternative options and express willingness to work with your employer to minimize any impact on operations while meeting your religious needs.