Invisible disabilities affect an estimated 10% of the 61 million Americans who live with a physical or mental condition that limits their daily activities—yet these conditions often go unrecognized because they can’t be seen. From chronic pain and autoimmune disorders to mental health disabilities and neurological differences, invisible disabilities present unique challenges when it comes to workplace discrimination and accommodation requests. The good news? Federal and state laws provide robust protections—if you know how to use them.

Key Takeaways

- Invisible disabilities include conditions like chronic pain, autoimmune disorders, ADHD, anxiety, depression, and chronic fatigue that substantially limit major life activities.

- The ADA defines disability broadly to protect episodic and non-apparent conditions, including those controlled by medication.

- Employees have the right to reasonable accommodations regardless of whether their disability is visible.

- Disclosure decisions are personal—you control when, how, and to whom you reveal your condition.

- Documentation and communication are critical for protecting your rights when facing skepticism or discrimination.

Disclaimer: This article provides general information for informational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for legal advice. It is essential to consult with an experienced employment lawyer at our law firm to discuss the specific facts of your case and understand your legal rights and options. This information does not create an attorney-client relationship.

What Conditions Qualify as Invisible Disabilities?

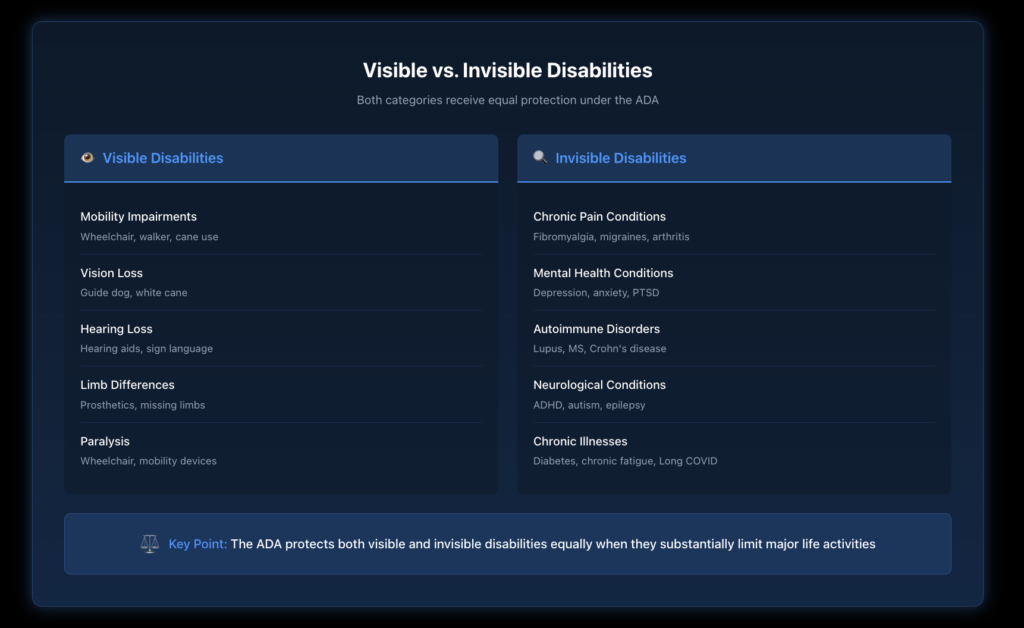

Invisible disabilities encompass a wide range of physical and mental conditions that substantially limit one or more major life activities but aren’t immediately apparent to others. Understanding which conditions qualify helps employees recognize when they’re entitled to workplace protections.

What Are Common Types of Invisible Disabilities?

The spectrum of invisible disabilities includes conditions across multiple categories. Chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia, migraine disorders, and arthritis affect millions of workers who may appear healthy but experience significant daily limitations. Autoimmune disorders, including multiple sclerosis, lupus, and Crohn’s disease, can cause debilitating fatigue and unpredictable symptom flares.

Mental health conditions represent one of the largest categories of invisible disabilities. Depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and bipolar disorder all qualify for protection when they substantially limit major life activities like concentrating, thinking, or sleeping. The EEOC has specifically addressed psychiatric disabilities under the ADA, confirming their protected status.

Neurological conditions, including ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injuries, also fall under the invisible disability umbrella. These conditions often affect cognitive functions, sensory processing, and executive functioning in ways that aren’t visible to coworkers or supervisors.

Chronic illnesses such as diabetes, Long COVID, heart conditions, and chronic fatigue syndrome round out the major categories. These conditions can cause fatigue, dizziness, and other symptoms that fluctuate in intensity—sometimes allowing normal functioning and other times creating significant impairment.

Why Are These Disabilities Called “Invisible”?

The term “invisible” refers to the fact that these conditions don’t produce obvious physical markers. Unlike someone using a wheelchair or a cane, a person with fibromyalgia or an anxiety disorder may appear completely healthy even while experiencing severe symptoms.

According to Harvard Health, only a fraction of Americans with disabilities use visible supports like wheelchairs or canes, meaning most people with disabilities don’t appear disabled. This creates unique challenges in the workplace, where colleagues and supervisors may question the legitimacy of conditions they cannot observe.

The variability of many invisible disabilities adds another layer of complexity. Someone with multiple sclerosis might function well on Monday and struggle to walk by Wednesday. This episodic nature often leads to skepticism and accusations of “faking it,” making legal protections especially important.

How Does the ADA Protect Invisible Disabilities?

The Americans with Disabilities Act provides the primary federal framework for protecting employees with invisible disabilities. Understanding these protections is essential for advocating effectively in the workplace.

What Is the ADA’s Definition of Disability?

The ADA defines a disability as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” This intentionally broad definition encompasses conditions that may not be visible but significantly affect functions like concentrating, thinking, communicating, sleeping, or the operation of bodily systems.

The ADA Amendments Act of 2008 significantly expanded protections for people with invisible disabilities by clarifying that the definition should be construed broadly in favor of coverage. The amendments established that episodic conditions are covered when active and that mitigating measures like medication should not be considered when determining disability status.

Major life activities now explicitly include mental processes such as thinking, concentrating, and communicating—directly relevant to many invisible conditions. The operation of major bodily functions, including the immune system, neurological system, and circulatory system, also qualifies.

Which Employers Must Comply with the ADA?

Title I of the ADA applies to private employers with 15 or more employees, as well as state and local governments, employment agencies, and labor unions. Federal employees receive similar protections under Section 501 of the Rehabilitation Act.

The law prohibits discrimination in all employment practices, including hiring, firing, promotions, compensation, training, and other terms and conditions of employment. For employees with invisible disabilities, this means employers cannot refuse to hire you, demote you, or terminate you based on your disability—even if that disability isn’t visible.

How Do New York Laws Expand These Protections?

New York State Human Rights Law and New York City Human Rights Law provide broader protections than federal law. These state and local laws define disability more inclusively and place a greater burden on employers to prove they cannot reasonably accommodate an employee.

Importantly, New York laws cover smaller employers not reached by the ADA and may provide additional remedies for discrimination. Employees in New York often have stronger claims under state law than they would under federal protections alone.

How Do You Request Accommodations for an Invisible Disability?

The right to reasonable accommodations is fundamental to disability protection. For invisible disabilities, navigating the accommodation process requires careful communication and documentation.

What Counts as a Reasonable Accommodation?

Reasonable accommodations are modifications to the job or work environment that enable a qualified individual with a disability to perform essential job functions. According to the Job Accommodation Network, 58% of accommodations cost nothing to implement, and most others involve only a modest one-time expense.

For invisible disabilities, common accommodations include flexible scheduling or modified work hours to accommodate medical appointments or symptom fluctuations. Remote work arrangements can eliminate commuting stress and allow better symptom management. Adjusted lighting, reduced noise levels, and private workspaces help employees with sensory sensitivities or concentration difficulties.

Other accommodations might include breaks scheduled around medication timing, ergonomic equipment, modified communication methods, or the reallocation of marginal job duties. The key is identifying what specific barriers your disability creates and requesting modifications that address those barriers.

What Is the Interactive Process?

Once you request an accommodation, your employer must engage in an “interactive process“—a collaborative dialogue to determine appropriate accommodations. This process involves discussing your specific limitations, exploring potential options, and selecting the most effective accommodation.

Your employer may request medical documentation to verify your disability and need for accommodation. However, they can only request information relevant to your accommodation request—not your complete medical history. Work with your healthcare provider to ensure documentation confirms your condition, describes functional limitations, and explains accommodation needs without unnecessary medical details.

The interactive process should be a good-faith discussion. While your employer doesn’t have to provide the exact accommodation you request, they must genuinely consider your input. If they propose an alternative, it should be equally effective at addressing your limitations.

When Can Employers Deny Accommodation Requests?

Employers can deny accommodations only when they would cause “undue hardship“—meaning significant difficulty or expense considering the employer’s size, financial resources, and business needs. An employer cannot refuse simply because an accommodation involves some cost.

For invisible disabilities specifically, employers sometimes deny requests based on skepticism about the condition itself. This is not a valid basis for denial. If you provide appropriate medical documentation and your requested accommodation is reasonable, your employer must engage in the interactive process regardless of whether they can “see” your disability.

Should You Disclose Your Invisible Disability at Work?

Perhaps the most difficult decision facing employees with invisible disabilities is whether, when, and how to disclose their condition. Unlike visible disabilities, you may have the option to keep your condition private.

What Are the Benefits and Risks of Disclosure?

Disclosure provides legal protections and access to accommodations—but it also exposes you to potential bias and skepticism. According to a 2017 study by the Center for Talent Innovation, among white-collar employees with disabilities, 62% have invisible conditions, but only 3.2% self-identify to employers.

The benefits of disclosure include the ability to request reasonable accommodations, legal protection against discrimination and retaliation, and the freedom to discuss your needs openly. Without disclosure, you cannot claim accommodation denials or disability discrimination.

The risks involve potential unconscious bias, skepticism from supervisors and coworkers, and the possibility of being perceived differently. Some employees fear disclosure will limit their advancement opportunities or lead to exclusion from important projects.

When Is the Right Time to Disclose?

Timing disclosure is highly personal. Options include disclosing during the application process (only necessary if you need interview accommodations), after receiving a job offer, when starting a new position, when accommodation needs arise, after establishing yourself in the role, or when performance issues related to your disability emerge.

Disclosing earlier provides legal protections sooner, but may trigger bias before you’ve demonstrated your capabilities. Disclosing later lets you prove your value first, but may lead to preventable performance issues. Many experts suggest disclosing when you need accommodations—not before.

How Much Information Must You Share?

You control how much information to disclose. The law only requires you to inform your employer that you have a disability requiring accommodation—not your specific diagnosis or complete medical history. You can share as many or as few details as you’re comfortable with.

You also control who receives this information. While HR and direct supervisors may need to know about accommodation requirements, you can typically request that your specific condition remain confidential. Your employer has an obligation to keep medical information separate from personnel files.

What Does Discrimination Against Invisible Disabilities Look Like?

Disability discrimination against employees with invisible conditions often takes subtle forms that can be difficult to recognize—and even harder to prove.

What Are Common Forms of Discrimination?

Failure to accommodate represents one of the most common violations. This includes rejecting reasonable accommodation requests without proper consideration, delaying implementation indefinitely, or providing inadequate accommodations that don’t actually address your limitations.

Harassment based on invisible disabilities frequently involves questioning the legitimacy of your condition. Comments like “you don’t look sick,” “everyone gets tired sometimes,” or “you just need to push through” may indicate discriminatory attitudes. Pressure to disclose detailed medical information or mockery of accommodation needs also constitutes harassment.

Adverse employment actions—termination, demotion, unfavorable assignments, or denial of promotions—based on disability status are prohibited. For invisible disabilities, these actions often follow accommodation requests or are disguised as performance-based decisions.

Privacy violations occur when employers share your confidential medical information with those who don’t need it. Retaliation happens when you face negative consequences after requesting accommodations or asserting your rights.

How Do You Document Discrimination?

Effective documentation is crucial for invisible disability cases because the discrimination itself is often subtle. Record discriminatory incidents with dates, times, locations, participants, witnesses, and verbatim statements. Save emails, messages, and any written communications related to your disability or accommodation requests.

Keep copies of all accommodation requests and responses. Document performance reviews, especially those showing your capabilities. Note any concerning comments or changes in treatment following disclosure or accommodation requests.

This documentation creates a paper trail that proves invaluable if disputes arise. Because invisible disabilities can’t be seen, having thorough records becomes even more important for establishing that discrimination occurred.

What Should You Do If You Face Discrimination?

If you believe you’re experiencing disability discrimination, taking prompt action protects your rights and preserves your legal options.

What Internal Steps Should You Take First?

Start by reviewing your employee handbook to understand the company’s complaint procedures. Report discrimination to HR or appropriate supervisors following established protocols. Continue performing your job to the best of your ability while the issue is addressed.

Document everything—from your initial report to the company’s response and any subsequent treatment changes. Request written confirmation of any meetings or decisions. If discrimination continues after reporting, document that as well.

When Should You File an External Complaint?

External complaints have strict time limitations—typically 180 to 300 days, depending on your state. If internal processes don’t resolve the issue, consider filing with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or your state’s fair employment agency.

The EEOC investigates charges and may attempt to resolve them through mediation or conciliation. If the agency doesn’t find discrimination or resolution fails, you’ll receive a “right to sue” letter allowing you to proceed to court.

Consulting with an employment attorney experienced in disability discrimination helps you understand your options and develop an effective strategy. An attorney can advise whether your situation warrants a complaint and guide you through the process.

What Remedies Are Available for Discrimination?

Available remedies may include back pay for lost wages, front pay when reinstatement isn’t feasible, compensatory damages for emotional distress, and, in some cases, punitive damages. Proving disability discrimination typically requires showing you have a qualifying disability, you were qualified for your position, and you experienced adverse action because of your disability.

Court orders may require reinstatement, accommodation implementation, or policy changes. If you prevail, you may also recover attorney’s fees and costs.

Ready to Protect Your Rights?

Living with an invisible disability presents unique workplace challenges, but understanding your legal protections empowers you to advocate effectively for yourself. Whether you need help requesting accommodations, responding to discrimination, or filing a complaint, experienced legal guidance makes a difference.

If you’re facing challenges related to an invisible disability at work—accommodation denials, skepticism, harassment, or discrimination—Nisar Law Group can help. Our employment law attorneys have extensive experience protecting employee rights across New York and New Jersey. Contact us today for a confidential consultation to discuss your situation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Invisible Disabilities

Yes, ADHD qualifies as an invisible disability under the ADA when it substantially limits major life activities such as concentrating, learning, or working. Many adults with ADHD appear to function normally but struggle with executive functioning, focus, and organization in ways that significantly impact their work performance. Employees with ADHD are entitled to reasonable accommodations like written instructions, flexible deadlines, reduced distractions, or permission to use organizational tools.

Chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia represent classic non-visible disabilities. Someone with fibromyalgia may experience widespread pain, severe fatigue, and cognitive difficulties that significantly limit their ability to work—yet they typically appear healthy to outside observers. Other common examples include autoimmune disorders like lupus, mental health conditions like depression or anxiety, and neurological conditions like epilepsy or multiple sclerosis.

Anxiety disorders can qualify as invisible disabilities when they substantially limit major life activities. Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety, and PTSD all receive ADA protection when symptoms are severe enough to impair functioning. Accommodations might include a private workspace, flexible scheduling for therapy appointments, modified communication methods, or the ability to take breaks during high-stress periods.

While there’s no official list of “the 4 invisible disabilities,” the main categories include mental health conditions (depression, anxiety, PTSD), chronic illnesses (diabetes, Crohn’s disease, chronic fatigue), neurological conditions (ADHD, autism, epilepsy), and chronic pain conditions (fibromyalgia, arthritis, migraine disorders). Each category contains numerous specific conditions that may qualify for workplace protections depending on how they affect the individual.

Mental health conditions and chronic pain disorders are often considered the most challenging disabilities to prove because they lack objective diagnostic tests or visible symptoms. Unlike a broken bone that appears on an X-ray, conditions like depression, fibromyalgia, or chronic fatigue rely on reported symptoms and functional assessments. Thorough medical documentation, consistent treatment history, and clear descriptions of functional limitations help establish these conditions for accommodation and legal purposes.

“Silent disability” is another term for invisible or hidden disability—a condition that substantially limits major life activities without producing visible signs. The term emphasizes how these conditions allow people to suffer in silence because others cannot see their struggles. Silent disabilities include hearing impairments, chronic illnesses, mental health conditions, and learning disabilities. The terminology highlights the isolation many people feel when their very real limitations go unrecognized.

Most chronic illnesses present at least some of the time. Multiple sclerosis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic fatigue syndrome all cause significant impairment without obvious external signs. Even conditions that sometimes produce visible effects—like flares causing swelling or mobility aids—often have periods where the person appears completely healthy despite ongoing symptoms. This variability contributes to misunderstanding and skepticism in workplace settings.

Related Resources

- Reasonable Accommodations: What to Request and How

- What Qualifies as a Disability Under the ADA

- Mental Health Disabilities: Special Considerations

- Proving Disability Discrimination: Building Your Case

- When Employers Can Claim “Undue Hardship”

- Disability Discrimination in Remote Work Environments

- Long COVID as a Disability: Emerging Legal Considerations