Proving race discrimination at work doesn’t require catching your employer red-handed making racist statements. While direct evidence like explicit discriminatory remarks certainly helps, the reality is that most successful race discrimination cases are built on circumstantial evidence—patterns of treatment, statistical disparities, and timing that together paint a picture of unlawful bias. Understanding how courts evaluate both types of evidence is essential for building a compelling case under Title VII and Section 1981.

Key Takeaways

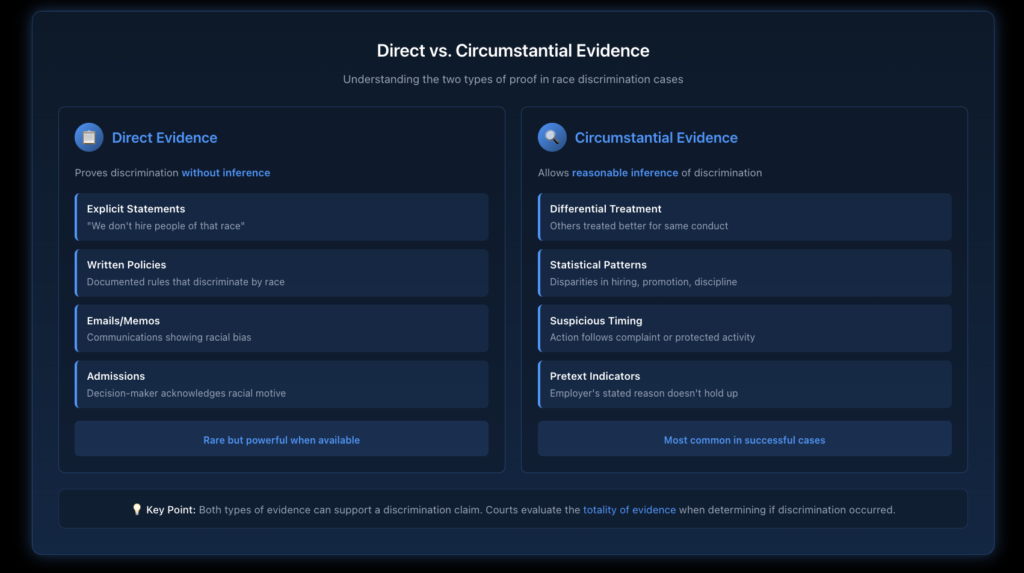

- Direct evidence directly proves discriminatory intent without requiring inference, but it’s rare in modern discrimination cases.

- Circumstantial evidence can be just as powerful as direct evidence when properly documented and presented.

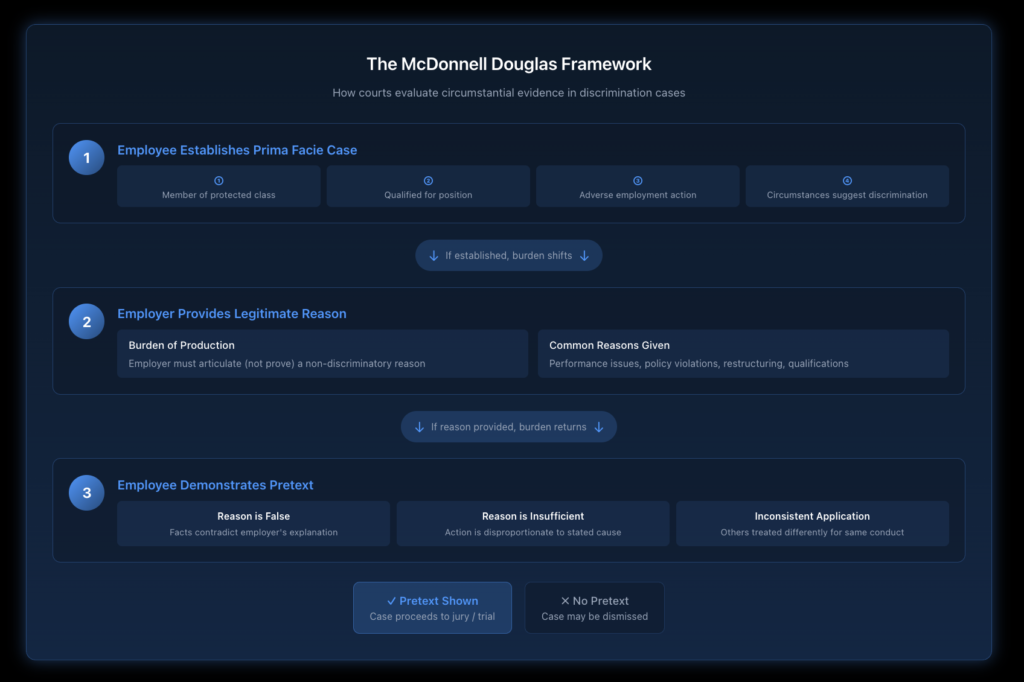

- The McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting framework is the primary method for proving discrimination through circumstantial evidence.

- New York State Human Rights Law provides stronger protections and longer filing deadlines than federal law.

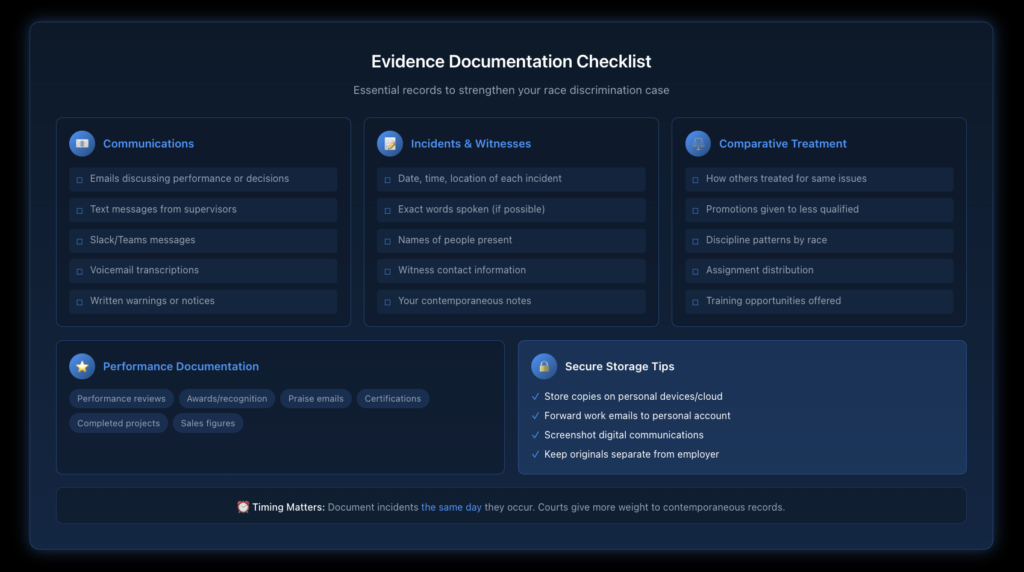

- Keeping detailed records of discriminatory treatment significantly strengthens your case.

Disclaimer: This article provides general information for informational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for legal advice. It is essential to consult with an experienced employment lawyer at our law firm to discuss the specific facts of your case and understand your legal rights and options. This information does not create an attorney-client relationship.

What Is Direct Evidence of Race Discrimination?

Direct evidence is exactly what it sounds like—proof that directly establishes discriminatory intent without requiring any inference or presumption. When a supervisor says, “We don’t promote Black employees to management positions,” or a company memo states, “don’t hire applicants from certain ethnic backgrounds,” that’s direct evidence.

Direct evidence typically falls into several categories. Written communications are among the most powerful forms, including emails, text messages, or memos that explicitly reference race in employment decisions. Verbal statements from decision-makers that directly link race to an adverse action also constitute direct evidence, though these require credible witnesses. Company policies that facially discriminate based on race—while increasingly rare—represent the clearest form of direct evidence.

The challenge with direct evidence is that modern employers rarely express bias so openly. Years of employment discrimination litigation have made most organizations careful about documented communications. When direct evidence does exist, it typically comes from informal settings, overheard conversations, or communications that decision-makers didn’t expect would become evidence.

What Is Circumstantial Evidence and Why Does It Matter?

Circumstantial evidence requires courts to draw inferences about discriminatory intent based on facts and patterns. Unlike direct evidence, it doesn’t prove discrimination outright but allows a factfinder to reasonably conclude that race was a motivating factor. According to EEOC guidance, circumstantial evidence is fully capable of supporting discrimination claims.

Consider this example: a qualified Black employee is passed over for promotion in favor of a less experienced white colleague, the employee recently complained about racial harassment, and the employer’s stated reason for the decision doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. No single fact proves discrimination, but together they create a compelling inference of racial bias.

Circumstantial evidence commonly includes comparative treatment of employees of different races in similar situations, statistical disparities in hiring, promotions, or terminations, suspicious timing between protected activity and adverse actions, inconsistent application of workplace policies, and evidence that the employer’s stated reason is pretextual.

How Does the McDonnell Douglas Framework Work?

The McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting framework is the standard method for evaluating circumstantial evidence in discrimination cases. Named after the 1973 Supreme Court case that established it, this three-step process structures how courts analyze discrimination claims.

First, the employee must establish a prima facie case. This means showing four elements: membership in a protected class (based on race), qualification for the position or satisfactory job performance, an adverse employment action (termination, demotion, discipline, etc.), and circumstances suggesting discrimination (such as replacement by someone outside the protected class or different treatment than similarly situated employees).

Once the employee establishes a prima facie case, the burden shifts to the employer to articulate a legitimate, non-discriminatory reason for the decision. This burden is relatively light—the employer just needs to produce evidence of a lawful reason, not prove it was the actual reason.

If the employer meets this burden, the employee then has the opportunity to demonstrate that the stated reason is pretextual—essentially a cover story for discrimination. This is often where cases are won or lost.

What Makes a Strong Prima Facie Case?

Building a strong prima facie case requires careful attention to each element. While the threshold is intentionally low to allow cases to proceed, stronger prima facie evidence creates momentum that carries through the entire case.

Documenting your qualifications is critical. This means maintaining records of performance reviews, awards, certifications, and any recognition of your work. When an employer later claims you were terminated or passed over due to performance issues, this documentation directly contradicts that narrative.

The adverse employment action must be significant enough to constitute a material change in employment conditions. Obvious examples include termination, demotion, or failure to hire. Less obvious but still actionable examples include significant changes in job duties, exclusion from important meetings or projects, denial of training opportunities, or transfers to less desirable positions.

Circumstances giving rise to an inference of discrimination often come from comparative evidence. If you can show that employees of a different race in similar situations received better treatment, that’s powerful evidence. The 80% rule in discrimination cases—where a selection rate for a protected group that’s less than 80% of the rate for the highest group creates an inference of adverse impact—can also support your claim in appropriate cases.

How Do You Prove an Employer's Reason Is Pretextual?

Demonstrating pretext—that the employer’s stated reason is not the real reason—is often the decisive battlefield in discrimination cases. There are several effective approaches to establishing a pretext.

Showing that the stated reason is factually false is the most direct approach. If your employer claims you were terminated for poor attendance but your records show perfect attendance, that directly undermines their credibility. Similarly, if they claim you lacked qualifications you actually possessed, that exposes the pretextual nature of their explanation.

Proving the reason is insufficient involves showing that the stated reason wouldn’t normally result in the adverse action. If your employer claims you were fired for a minor policy violation that typically results only in a warning, that inconsistency suggests the real motivation lies elsewhere.

Demonstrating inconsistent application shows that the employer treated similarly situated employees of different races differently for the same conduct. If white employees received warnings for the same behavior that got you terminated, that’s strong evidence of pretext. Cases involving hostile work environment claims often reveal these patterns of disparate treatment.

What Is the 80% Rule in Discrimination Cases?

The 80% rule, also known as the four-fifths rule, provides a statistical framework for identifying potential discrimination in employment practices. It states that a selection rate for any racial group that is less than 80% (four-fifths) of the rate for the group with the highest rate creates an inference of adverse impact.

For example, if an employer hires 50% of white applicants but only 30% of Black applicants, the selection rate for Black applicants (30%) is only 60% of the white applicant rate (50%)—well below the 80% threshold. This statistical disparity can support a discrimination claim.

The 80% rule is particularly useful in cases involving systemic discrimination patterns or challenges to facially neutral policies that disproportionately affect certain racial groups. However, it’s one tool among many and should be combined with other evidence to build the strongest possible case.

What Special Protections Does New York Law Provide?

New York offers significantly stronger protections against race discrimination than federal law. The New York State Human Rights Law and New York City Human Rights Law both provide broader coverage and more plaintiff-friendly standards.

Under the NYC Human Rights Law, employees only need to show that race was “a motivating factor” in the adverse action—a lower bar than the federal standard. The state law also covers employers with as few as four employees, compared to Title VII’s 15-employee threshold. Filing deadlines are more generous, too: you have three years to file under state law compared to 300 days for an EEOC charge.

New York courts have interpreted state and city anti-discrimination laws more broadly than their federal counterparts. This means conduct that might not rise to the level of a federal violation could still be actionable under New York law. For employees facing race discrimination in New York, understanding these additional state protections is essential for strategic case development.

What Evidence Should You Document and Preserve?

Building a strong discrimination case starts long before you file a complaint. Systematic documentation can make the difference between a case that succeeds and one that fails.

Keep contemporaneous records of discriminatory incidents. Write down what happened, who was present, what was said, and when it occurred—ideally the same day. Courts give significant weight to notes made at or near the time of events compared to later recollections.

Preserve all relevant communications. This includes emails, text messages, voicemails, and any written correspondence related to your employment, performance, or the discriminatory treatment. If your employer uses messaging platforms like Slack or Teams, take screenshots of relevant conversations. Be aware of your company’s document retention policies and your legal right to preserve evidence.

Identify potential witnesses early. Other employees may have observed discriminatory conduct, heard biased statements, or experienced similar treatment. Record their names and contact information, though be cautious about directly soliciting testimony in ways that could be perceived as interfering with your employment.

Document your own performance thoroughly. Save copies of positive performance reviews, emails praising your work, awards or recognition, and any documentation of your qualifications and achievements. This evidence directly counters any later claim that adverse action was based on performance issues.

How Do Direct and Circumstantial Evidence Work Together?

Many successful discrimination cases combine elements of both direct and circumstantial evidence. A stray comment suggesting racial bias—even if not direct evidence by itself—can provide important context for circumstantial evidence. Similarly, strong circumstantial evidence can support the credibility of testimony about verbal statements.

Courts evaluate the totality of the evidence when determining whether discrimination occurred. This means you shouldn’t dismiss potential evidence because it doesn’t fit neatly into one category. A supervisor’s comment about “cultural fit,” combined with statistical disparities in promotion rates and evidence that your qualifications exceeded those of the promoted candidate, together create a stronger case than any single piece of evidence alone.

Cases involving discrimination by association often require combining different types of evidence to establish the connection between an employee’s relationships and the adverse treatment they experienced.

When Should You Consult an Employment Attorney?

If you’re experiencing race discrimination at work, consulting with an experienced employment attorney sooner rather than later provides several advantages. An attorney can help you understand the strength of your potential claims, develop a documentation strategy, navigate filing deadlines and procedural requirements, and protect you from retaliation.

Timing matters significantly in discrimination cases. Evidence can disappear, witnesses can forget details or leave the company, and filing deadlines are strictly enforced. The earlier you seek guidance, the better positioned you’ll be to protect your rights.

Many employees worry that consulting an attorney will escalate the situation or jeopardize their jobs. In reality, understanding your legal options empowers you to make informed decisions about how to proceed. A consultation doesn’t commit you to filing a lawsuit—it gives you information to decide what’s right for your situation.

Take Action to Protect Your Rights

If you’re facing race discrimination at work, you don’t have to navigate this challenge alone. Whether you have direct evidence of discrimination or need help building a case through circumstantial evidence, experienced legal counsel can help you understand your options and pursue the justice you deserve.

The attorneys at Nisar Law Group have extensive experience representing employees in race discrimination cases and understand the nuances of both federal and New York law. We can evaluate your situation, explain your legal rights, and develop a strategy tailored to your circumstances.

Contact Nisar Law Group today for a confidential consultation about your race discrimination case.

Frequently Asked Questions About Race Discrimination Evidence

Circumstantial evidence can absolutely be enough to win a race discrimination case. Courts have repeatedly held that circumstantial evidence can be just as persuasive as direct evidence, and the vast majority of successful discrimination cases rely primarily on circumstantial evidence. The key is building a comprehensive record that, taken together, allows a reasonable factfinder to conclude that discrimination occurred. Strong circumstantial evidence includes comparative treatment of employees, statistical patterns, suspicious timing, and proof that the employer’s stated reasons don’t hold up under scrutiny.

Direct evidence of racial discrimination includes explicit statements linking race to employment decisions, such as a supervisor saying they won’t promote someone because of their race. It also includes written policies that discriminate on the basis of race, documented communications expressing racial bias, and admissions by decision-makers that race influenced their choices. The defining characteristic of direct evidence is that it proves discriminatory intent without requiring any inference—the connection between race and the adverse action is explicit and unambiguous.

Filing deadlines vary depending on the agency and law you’re using. For federal EEOC complaints under Title VII, you generally have 300 days from the discriminatory act in states with a state or local fair employment agency, like New York. Under the New York State Human Rights Law, you have three years to file a complaint with the state Division of Human Rights or in court. The New York City Human Rights Law also provides a three-year statute of limitations. Because deadlines are strictly enforced and missing them can eliminate your claims entirely, consulting with an attorney promptly is essential.

In race discrimination cases, the employee ultimately bears the burden of proving that discrimination occurred. However, the McDonnell Douglas framework creates a shifting burden of production. First, the employee must establish a prima facie case. Then the employer must articulate a legitimate, non-discriminatory reason. Finally, the employee must show that the reason is pretextual. Throughout this process, the ultimate burden of persuasion—convincing the factfinder that discrimination actually occurred—remains with the employee, typically by a preponderance of the evidence (more likely than not).

Yes, you can prove discrimination without witnesses, though witnesses certainly strengthen a case when available. Documentary evidence like emails, performance reviews, and personnel records can be powerful. Statistical evidence showing disparate treatment patterns doesn’t require witness testimony. Your own testimony about what you experienced and observed is evidence, and keeping contemporaneous notes significantly bolsters your credibility. An experienced attorney can help you identify and present the available evidence in the most compelling way, even without corroborating witnesses.

Retaliation for complaining about discrimination is itself illegal under federal and New York law. If you experience adverse treatment after making a discrimination complaint—whether internally or to an agency—document everything carefully, including the timing between your complaint and the retaliation. Report the retaliation through appropriate channels and consider adding a retaliation claim to any discrimination complaint. Retaliation claims are often easier to prove than the underlying discrimination claims because the timing between protected activity and adverse action creates a strong inference of retaliatory motive.

Courts look at whether employees share enough relevant characteristics to make a comparison meaningful. This typically includes similar job positions, similar supervisors or decision-makers, similar qualifications and experience levels, similar conduct or performance issues (if discipline is at issue), and being subject to the same policies. Employees don’t need to be identical, but they must be similar enough that differences in treatment can reasonably be attributed to race rather than legitimate business factors. The specific factors that matter most depend on the type of adverse action being challenged.